Alex Henshaw chatting with Winston Churchill at Castle Bromwich 1942. During the 6 years of WWII, Alex was responsible for testing the vast output of the Castle Bromwich factory. During the period 37,000 test flights took place, many of which were made by Alex.

Percival Mew Gull, G-AEXF which Alex Henshaw flew solo in 1939 from the UK- South Africa return,setting a time/speed record for the return trip which incredibly still stands today.

Percival Mew Gull, G-AEXF which Alex Henshaw flew solo in 1939 from the UK- South Africa return,setting a time/speed record for the return trip which incredibly still stands today.

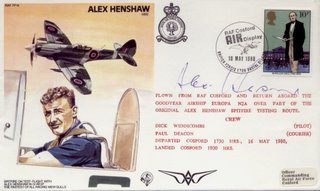

Alex Henshaw, Chief Spitfire Production Test Pilot at Supermarine Factory, Castle Bromwich.

Alex Henshaw, Chief Spitfire Production Test Pilot at Supermarine Factory, Castle Bromwich.

-->

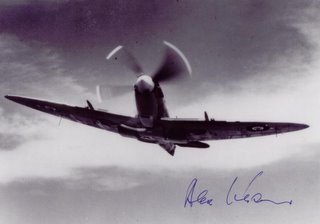

Alex Henshaw was an outstanding test pilot whose name will forever be associated with the Second World War's most famous aircraft, the Spitfire; between 1940 and 1945 he test flew some 2,360 individual Spitfires and Seafires (the naval version of the aircraft), amounting to more than 10 per cent of the total built.

By 1939 Henshaw was already celebrated as a pilot, having won the King's Cup Air Race and broken the record for a flight to Cape Town and back. When war broke out he volunteered for service with the RAF but, while waiting for his application to be processed, was invited instead to join Vickers at Weybridge as a test pilot.

At first he was put into Wellingtons and the Walrus; and, frustrated by the amount of administrative work, he was about to leave the company when he met Jeffrey Quill, the chief test pilot of Supermarine, who offered him a job.

After test flying Spitfires at the company's Southampton factory, Henshaw moved in June 1940 to the Vickers Armstrong (Supermarine) factory at Castle Bromwich, near Birmingham , where he was soon appointed chief production test pilot for Spitfires and Lancasters.

It could be dangerous work. Henshaw suffered a number of engine failures, and on one occasion, while flying over a built-up area, he crash-landed between two rows of houses.

The wings of his aircraft sheared off, and the engine and propeller finished up on someone's kitchen table. Henshaw - who sustained only minor injuries - was left sitting in the small cockpit section, which fortunately remained intact.

Only on one occasion was he forced to bale out, when the engine of his Spitfire exploded. Henshaw was thrown out of the aircraft by the blast and became entangled in his parachute, which was badly torn and held together by a single thread on its perimeter; the thread held, and he landed safely.

Castle Bromwich was not ideally suited to have an aerodrome; it was often blanketed in fog and a heavy industrial haze, closing the airfield for routine flying.

With 320 Spitfires being produced each month, however, test flying had to continue, and Henshaw developed his own technique for landing: as he made his approach he would use the columns of condensation rising from the four cooling towers at nearby Hemshall to locate the airfield and align him with the runway.

No other pilot was authorised to fly in these conditions, and Henshaw sometimes tested 20 aircraft in a day.

Once he was asked to put on a show for the Lord Mayor of Birmingham 's Spitfire Fund by flying at high speed above the city's main street. The civic dignitaries were furious when he inverted the aircraft, flying upside down below the top of the Council House.

Often he would be called upon to demonstrate the Spitfire to groups of visiting VIPs. After one virtuoso display Winston Churchill was so enthralled by his performance that he kept a special train waiting while they talked alone. Henshaw, for his part, considered Churchill "the greatest Englishman of all time, the man who saved the world".

Henshaw also tested other aircraft, including more than 300 Lancasters - he once famously barrel-rolled the big bomber, the only pilot to have pulled off this feat. But his great love remained the Spitfire, which he described as a "sheer dream".

For his services during the war Henshaw was appointed MBE. There were many who thought this a meagre reward for his contribution.

The son of a wealthy businessman, Alex Henshaw was born at Peterborough on November 7 1912 and educated at Lincoln Grammar School .

As a boy he was fascinated by flying and by motorcycles, and with financial support from his father - who thought it safer to be in an aircraft than on a motorcycle - he learned to fly in 1932 at the Skegness and East Lincolnshire Aero Club.

After his first solo his father gave him a de Havilland Gypsy Moth, and he made rapid progress as a pilot; the following year he felt competent to enter the King's Cup Air Race as one of the youngest-ever competitors.

The King's Cup was the most prestigious air race of the period and attracted enormous public interest. In 1934 Henshaw was invited to take part in his Miles Hawk Major. His prototype engine failed as he crossed the Irish Sea , and he was forced to ditch.

The next year he bought an Arrow Active, an aerobatic bi-plane. While he was performing an inverted loop, however, there was an explosion and the aircraft caught fire; Henshaw was forced to bale out, using the parachute he had been given on his birthday four weeks earlier.

In 1937 he won the inaugural London-to-Isle of Man air race in atrocious weather. Finally, in 1938, flying a Percival Mew Gull, he won the King's Cup at the age of 25, setting an average speed of 236.25 mph , a record that stands almost 70 years later.

Early in 1939 Henshaw made his record-breaking solo flight from England to Cape Town and back. In the spring of the previous year, accompanied by his father, he had surveyed possible routes down the eastern and western sides of Africa .

On February 5 1939 he took off in the Mew Gull from Gravesend to fly the western route. The aircraft had nine hours' endurance, and his first stop was at Oran , in Algeria , before a 1,300-mile leg across the Sahara . Without navigation or radio aids, he made further st ops in the Belgian Congo and Angola before reaching Cape Town , having flown 6,030 miles in just under 40 hours, a record.

After 28 hours in Cape Town , Henshaw set off on the return journey, following a similar route. Just after lunch on February 9 he landed at Gravesend , four days, 10 hours and 16 minutes after his departure. Having completed one of the greatest ever solo long distance flights, he was on the verge of collapse, and had to be lifted from the tiny cockpit.

He had broken the homeward record, established in a twin-engine aircraft flown by two pilots, by seven hours, and the out-and-return time by almost 31 hours. Henshaw's epic flight was, however, overshadowed by the imminence of war and, unlike those pioneers who preceded him by a few years, he received no public recognition.

After the war Henshaw went to South Africa as a director of Miles Aircraft, but returned to England in 1948 and joined his family's farming and holiday business. He redeveloped six miles of Lincolnshire coastline which had been requisitioned during the war; the project included an 18-hole golf course.

A residential estate at Sandilands bears the name Henshaw for the main avenue, while all the roads and streets are named for the various aircraft he flew.

In his youth he received a Royal Humane Society award for saving a boy from the River Witham, and in 1953, he was awarded the Queen's Commendation for Bravery following his rescue work during the great floods.

Henshaw remained in great demand at aviation functions to the end of his life. In his 90th year he gave a masterly presentation, without the aid of notes, at an event in London to commemorate 100 years of flight. During the evening Prince Philip invested him as a Companion of the Air League.

In the summer of 2005 he donated his papers, art collection, photographs and trophies to the RAF Museum , where he paid for a curator to catalogue and promote his collection, which reflects the "golden age" of flying.

To mark the 70th anniversary of the first flight of the Spitfire, in March 2006, the 93-year-old Henshaw flew over Southampton in a two-seater Spitfire, taking the controls once airborne. His pilot commented that Henshaw could have landed the aircraft but for the prohibitive insurance conditions.

Henshaw was a tough-minded man, but was also an approachable and patient one who took a great interest in promoting "air-mindedness" in young people, for which the Air League awarded him the Jeffery Quill Medal in 1997.

The Royal Aeronautical Society elected him an honorary fellow in 2003. He was a vice-president of the Spitfire Memorial Defence Fellowship in Canberra , Australia .He wrote three books about his experiences: The Flight of the Mew Gull; Sigh for a Merlin; and Wings over the Great Divide.