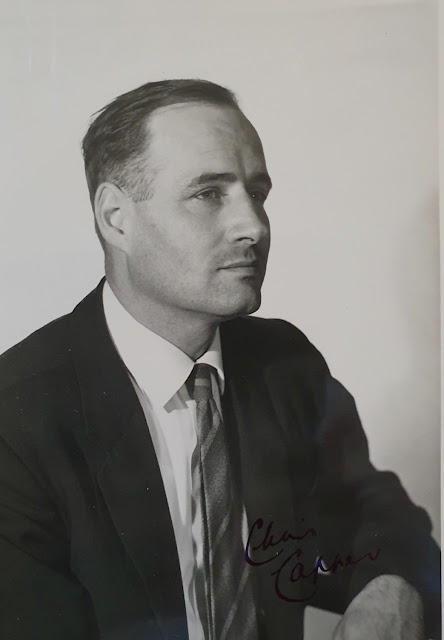

Chris Capper was a survivor of the test flying decade that followed the Second World War, when new designs of both military and civil aircraft were augmented by a wide variety of pure research projects. Among these were the de Havilland 108 tailless research aircraft whose role was to guide the design team then in the early stages of creating the Comet airliner.

The war years had seen the steady development of high-powered piston-engined aircraft but in a surprisingly short time these were to be replaced by jets. Into this transitional era Chris Capper graduated as a pilot, gaining his wings in Alberta in March 1943, and demonstrated his prowess by immediately becoming a flying instructor and remaining in Canada.. On completion of that tour he underwent a conversion course to fly the Mosquito, de Havilland’s superbly efficient light bomber and fighter design. Arriving in the Far East theatre only days after VJ-Day, Capper found no continuing role for the Mosquito and was fortunate to be chosen to become the test pilot at a maintenance unit near Allahabad.

Capper was reunited with the Mosquito for a tour on No 4 Squadron in Germany but the testing bug had bitten and he applied, successfully, to attend the Empire Test Pilots’ School. In March 1948 he began what he described as “the hardest nine month’s work I had ever done”. The variety of aircraft with which the School was equipped at the time hints at the versatility required of its graduates. To the everyday Harvard, Oxford, Anson, Auster, Firefly and Tempest could be added the four-engined Lincoln bomber for heavyweight experience and various versions of the Meteor and Vampire jet fighters. All these had to be approached in an analytical manner, the days being further filled by extensive lectures on performance and theory of flight..

It was a measure of Chris Capper’s quality that he was posted to probably the most arduous role available, Aero Flight at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough, and here he met the de Havilland 108.. He flew 51 sorties on the two aircraft. In an unusual publicity move and as a change from delicate low-speed handling investigations, Capper flew one of the research aircraft to Hatfield to be parked in front of the Comet while it was prepared for its first flight. Sadly both the 108s on the flight were lost in quick succession together with their pilots – a sad reminder of the extent to which test pilots were pushing the boundaries at that time. He remained on the flight for a further two years and, as a result of his work, was awarded the Air Force Cross. He himself commented on his luck at having such a wide variety of types to fly; in one month his log book records his flying 17 different types, an experience shared by very few current pilots.

The end of his time at Farnborough was also to be the end of his service in the Royal Air Force since his next posting was to be to a desk; this, he said, “had no appeal at all for me.” He had acquired some helicopter experience while at Farnborough and now spent nine months flying rotary-wing types with the Bristol Aircraft Company during which, as a sideline, he occupied the right-hand seat in the prototype Bristol Brabazon airliner on two occasions.

Following the disastrous loss of the DH 110 fighter prototype and its crew during the 1952 SBAC Show at Farnborough, Capper was invited by Hatfield’s Chief Test Pilot, John Cunningham, to fill the test-pilot vacancy and began a period of no less than 32 years continuous testing. To start with, the trainer version of the Vampire was under development together with variants of its successor, the Venom, but little more than a year later the second prototype DH 110 was ready to restart the test programme. The naval version of this aircraft was developed and produced (as the Sea Vixen) at the de Havilland facility at Christchurch, Hants, The company established a flight-test centre at Hurn and Capper spent six years there, latterly in charge of the Mark Two Sea Vixen programme. To the conventional airframe and engine performance and proving tests there now was added an increasing amount of weapons-system proving. In 1960 the company decided to vacate Hurn apart from launching the first flight of Christchurch-built production aircraft (at the end of the flight these were landed at Hatfield) and Capper returned to Hatfield which now had a new name over the door – Hawker Siddeley.

Military projects were steadily declining in number and Hatfield concentrated its effort on the civil world. Two programmes were advancing simultaneously – the Trident airliner and the HS125 business jet. Capper was given the 125 as his own, unusually being given the first flight because of John Cunningham’s workload in bringing on the Trident. Thereafter he stayed with the aircraft through its many refinements and different versions even transferring to become Chief Test Pilot at Chester when the manufacturer diversified all 125 activity there in 1966. This move gave him custody of the company’s private Mosquito on which he made his last flight in August 1981. His civil flying earned him a Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Services in the Air.

Capper’s aviation career continued until a normal retirement date at 65 , the last few years being spent as Airport Manager at Hatfield.

Chris Capper was a survivor of the test flying decade that followed the Second World War, when new designs of both military and civil aircraft were augmented by a wide variety of pure research projects. Among these were the de Havilland 108 tailless research aircraft whose role was to guide the design team then in the early stages of creating the Comet airliner.

The war years had seen the steady development of high-powered piston-engined aircraft but in a surprisingly short time these were to be replaced by jets. Into this transitional era Chris Capper graduated as a pilot, gaining his wings in Alberta in March 1943, and demonstrated his prowess by immediately becoming a flying instructor and remaining in Canada.. On completion of that tour he underwent a conversion course to fly the Mosquito, de Havilland’s superbly efficient light bomber and fighter design. Arriving in the Far East theatre only days after VJ-Day, Capper found no continuing role for the Mosquito and was fortunate to be chosen to become the test pilot at a maintenance unit near Allahabad.

Capper was reunited with the Mosquito for a tour on No 4 Squadron in Germany but the testing bug had bitten and he applied, successfully, to attend the Empire Test Pilots’ School. In March 1948 he began what he described as “the hardest nine month’s work I had ever done”. The variety of aircraft with which the School was equipped at the time hints at the versatility required of its graduates. To the everyday Harvard, Oxford, Anson, Auster, Firefly and Tempest could be added the four-engined Lincoln bomber for heavyweight experience and various versions of the Meteor and Vampire jet fighters. All these had to be approached in an analytical manner, the days being further filled by extensive lectures on performance and theory of flight..

It was a measure of Chris Capper’s quality that he was posted to probably the most arduous role available, Aero Flight at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough, and here he met the de Havilland 108.. He flew 51 sorties on the two aircraft. In an unusual publicity move and as a change from delicate low-speed handling investigations, Capper flew one of the research aircraft to Hatfield to be parked in front of the Comet while it was prepared for its first flight. Sadly both the 108s on the flight were lost in quick succession together with their pilots – a sad reminder of the extent to which test pilots were pushing the boundaries at that time. He remained on the flight for a further two years and, as a result of his work, was awarded the Air Force Cross. He himself commented on his luck at having such a wide variety of types to fly; in one month his log book records his flying 17 different types, an experience shared by very few current pilots.

The end of his time at Farnborough was also to be the end of his service in the Royal Air Force since his next posting was to be to a desk; this, he said, “had no appeal at all for me.” He had acquired some helicopter experience while at Farnborough and now spent nine months flying rotary-wing types with the Bristol Aircraft Company during which, as a sideline, he occupied the right-hand seat in the prototype Bristol Brabazon airliner on two occasions.

Following the disastrous loss of the DH 110 fighter prototype and its crew during the 1952 SBAC Show at Farnborough, Capper was invited by Hatfield’s Chief Test Pilot, John Cunningham, to fill the test-pilot vacancy and began a period of no less than 32 years continuous testing. To start with, the trainer version of the Vampire was under development together with variants of its successor, the Venom, but little more than a year later the second prototype DH 110 was ready to restart the test programme. The naval version of this aircraft was developed and produced (as the Sea Vixen) at the de Havilland facility at Christchurch, Hants, The company established a flight-test centre at Hurn and Capper spent six years there, latterly in charge of the Mark Two Sea Vixen programme. To the conventional airframe and engine performance and proving tests there now was added an increasing amount of weapons-system proving. In 1960 the company decided to vacate Hurn apart from launching the first flight of Christchurch-built production aircraft (at the end of the flight these were landed at Hatfield) and Capper returned to Hatfield which now had a new name over the door – Hawker Siddeley.

Military projects were steadily declining in number and Hatfield concentrated its effort on the civil world. Two programmes were advancing simultaneously – the Trident airliner and the HS125 business jet. Capper was given the 125 as his own, unusually being given the first flight because of John Cunningham’s workload in bringing on the Trident. Thereafter he stayed with the aircraft through its many refinements and different versions even transferring to become Chief Test Pilot at Chester when the manufacturer diversified all 125 activity there in 1966. This move gave him custody of the company’s private Mosquito on which he made his last flight in August 1981. His civil flying earned him a Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Services in the Air.

Capper’s aviation career continued until a normal retirement date at 65 , the last few years being spent as Airport Manager at Hatfield.

Chris Capper was a survivor of the test flying decade that followed the Second World War, when new designs of both military and civil aircraft were augmented by a wide variety of pure research projects. Among these were the de Havilland 108 tailless research aircraft whose role was to guide the design team then in the early stages of creating the Comet airliner.

The war years had seen the steady development of high-powered piston-engined aircraft but in a surprisingly short time these were to be replaced by jets. Into this transitional era Chris Capper graduated as a pilot, gaining his wings in Alberta in March 1943, and demonstrated his prowess by immediately becoming a flying instructor and remaining in Canada.. On completion of that tour he underwent a conversion course to fly the Mosquito, de Havilland’s superbly efficient light bomber and fighter design. Arriving in the Far East theatre only days after VJ-Day, Capper found no continuing role for the Mosquito and was fortunate to be chosen to become the test pilot at a maintenance unit near Allahabad.

Capper was reunited with the Mosquito for a tour on No 4 Squadron in Germany but the testing bug had bitten and he applied, successfully, to attend the Empire Test Pilots’ School. In March 1948 he began what he described as “the hardest nine month’s work I had ever done”. The variety of aircraft with which the School was equipped at the time hints at the versatility required of its graduates. To the everyday Harvard, Oxford, Anson, Auster, Firefly and Tempest could be added the four-engined Lincoln bomber for heavyweight experience and various versions of the Meteor and Vampire jet fighters. All these had to be approached in an analytical manner, the days being further filled by extensive lectures on performance and theory of flight..

It was a measure of Chris Capper’s quality that he was posted to probably the most arduous role available, Aero Flight at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough, and here he met the de Havilland 108.. He flew 51 sorties on the two aircraft. In an unusual publicity move and as a change from delicate low-speed handling investigations, Capper flew one of the research aircraft to Hatfield to be parked in front of the Comet while it was prepared for its first flight. Sadly both the 108s on the flight were lost in quick succession together with their pilots – a sad reminder of the extent to which test pilots were pushing the boundaries at that time. He remained on the flight for a further two years and, as a result of his work, was awarded the Air Force Cross. He himself commented on his luck at having such a wide variety of types to fly; in one month his log book records his flying 17 different types, an experience shared by very few current pilots.

The end of his time at Farnborough was also to be the end of his service in the Royal Air Force since his next posting was to be to a desk; this, he said, “had no appeal at all for me.” He had acquired some helicopter experience while at Farnborough and now spent nine months flying rotary-wing types with the Bristol Aircraft Company during which, as a sideline, he occupied the right-hand seat in the prototype Bristol Brabazon airliner on two occasions.

Following the disastrous loss of the DH 110 fighter prototype and its crew during the 1952 SBAC Show at Farnborough, Capper was invited by Hatfield’s Chief Test Pilot, John Cunningham, to fill the test-pilot vacancy and began a period of no less than 32 years continuous testing. To start with, the trainer version of the Vampire was under development together with variants of its successor, the Venom, but little more than a year later the second prototype DH 110 was ready to restart the test programme. The naval version of this aircraft was developed and produced (as the Sea Vixen) at the de Havilland facility at Christchurch, Hants, The company established a flight-test centre at Hurn and Capper spent six years there, latterly in charge of the Mark Two Sea Vixen programme. To the conventional airframe and engine performance and proving tests there now was added an increasing amount of weapons-system proving. In 1960 the company decided to vacate Hurn apart from launching the first flight of Christchurch-built production aircraft (at the end of the flight these were landed at Hatfield) and Capper returned to Hatfield which now had a new name over the door – Hawker Siddeley.

Military projects were steadily declining in number and Hatfield concentrated its effort on the civil world. Two programmes were advancing simultaneously – the Trident airliner and the HS125 business jet. Capper was given the 125 as his own, unusually being given the first flight because of John Cunningham’s workload in bringing on the Trident. Thereafter he stayed with the aircraft through its many refinements and different versions even transferring to become Chief Test Pilot at Chester when the manufacturer diversified all 125 activity there in 1966. This move gave him custody of the company’s private Mosquito on which he made his last flight in August 1981. His civil flying earned him a Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Services in the Air.

Capper’s aviation career continued until a normal retirement date at 65 , the last few years being spent as Airport Manager at Hatfield.